Resources

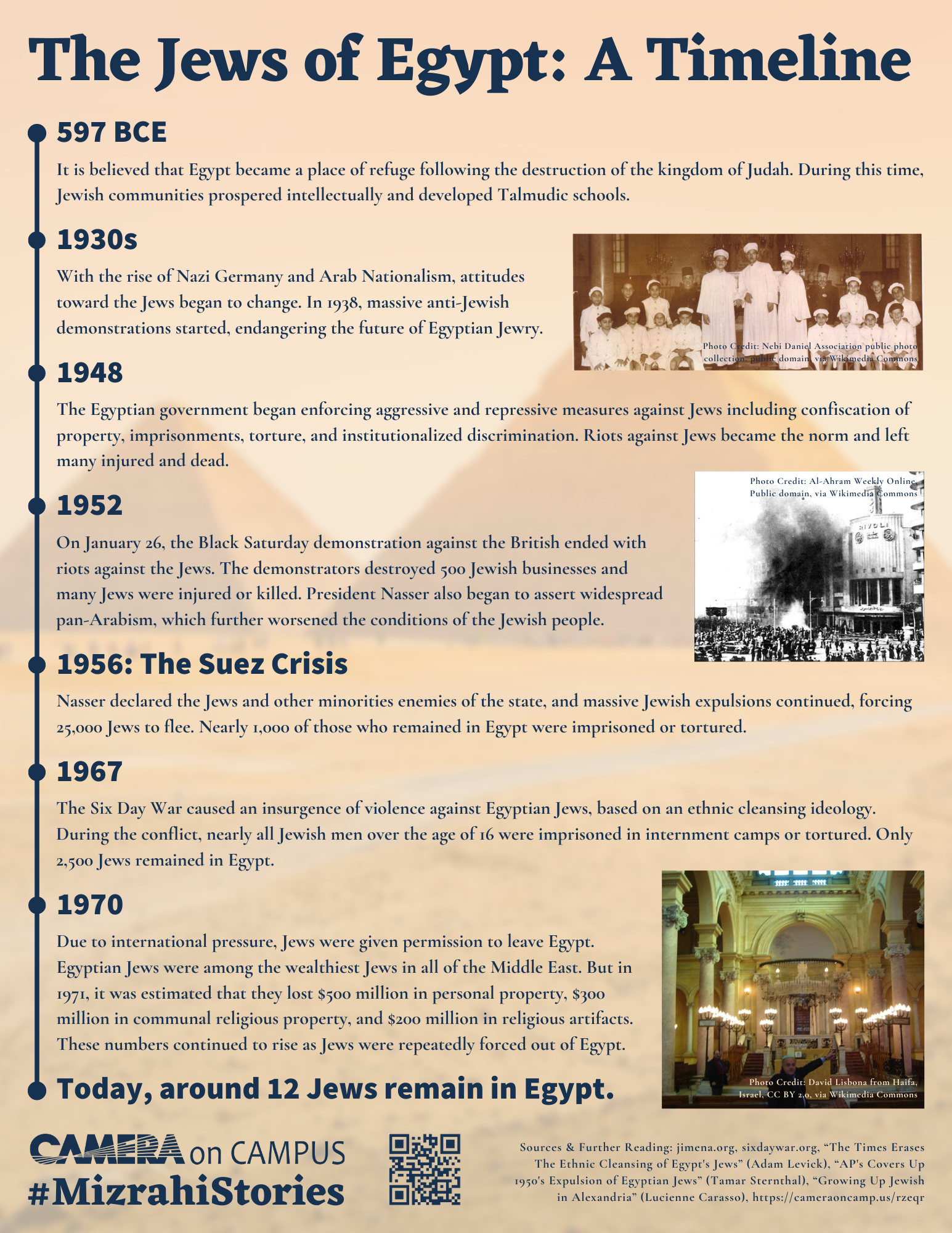

Lebanon

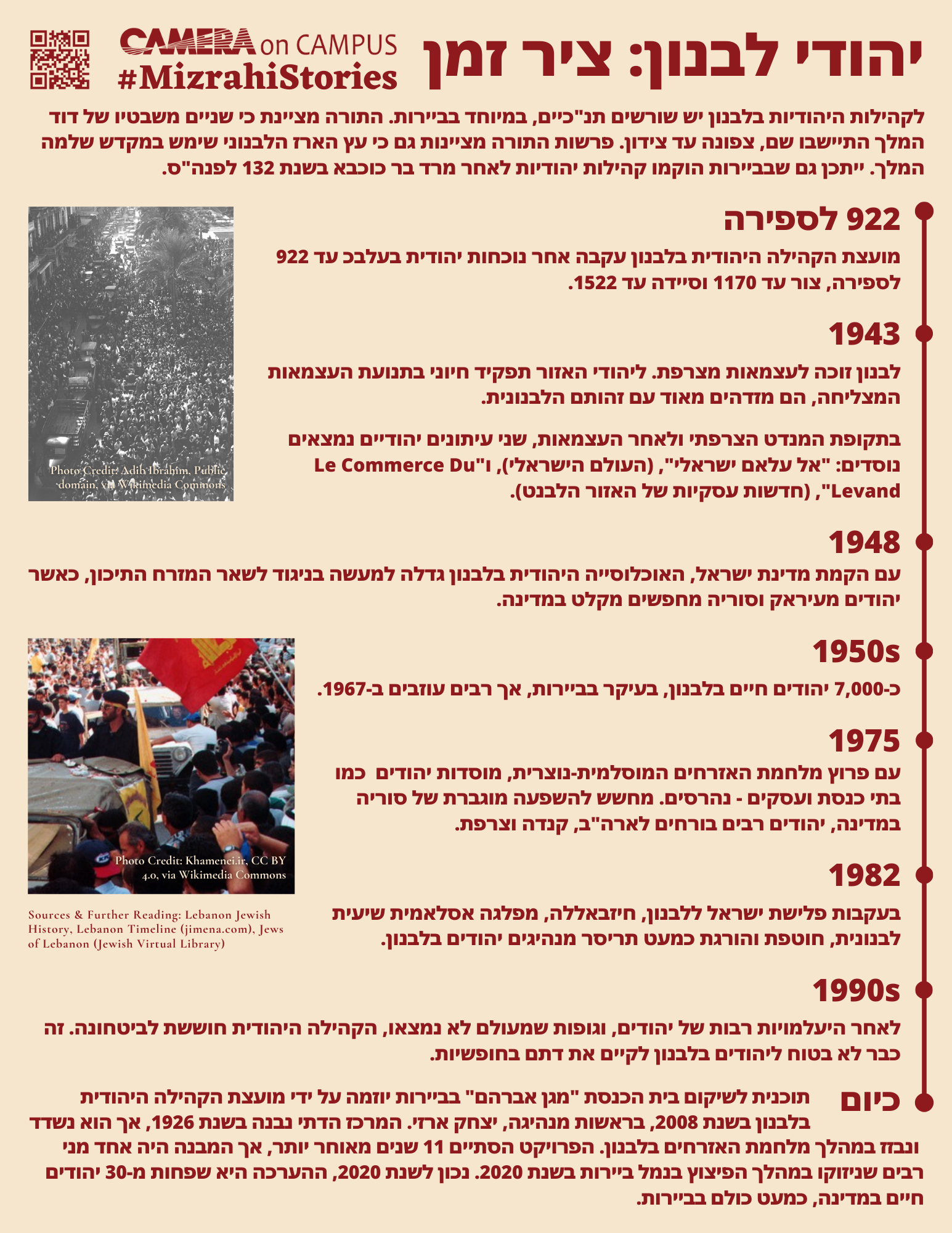

In 1948, there were 20,000 Jews living in Lebanon; in 2020, there were only 29 Jews still there. According to Jewish Virtual Library, "Nearly all of the remaining Jews are in Beirut, where there is a committee that represents the community.2 Because of the current political situation, Jews are unable to openly practice Judaism. In 2004, only 1 out of 5,000 Lebanese Jewish citizens registered to vote participated in the municipal elections. Virtually all of those registered have died or fled the country. The lone Jewish voter said that most of the community consists of old women."

WJC Affiliate

History

Jews have lived in Lebanon since ancient times. According to tradition, in the 1st century c.e., King Herod the Great had a temple constructed in the city of Tyre for his Jewish subjects living there and also supported the Jewish community in Beirut. The community grew, and by the 6th century, synagogues had been built in both Beirut and Tripoli. In the late 18th and 19th centuries, Jews mainly settled in villages in Lebanon, and most Jewish communities were interspersed with those of the Druze.During the first half of the current century, the community expanded tremendously due to immigration from Greece and Turkey, and later from Syria and Iraq. This continued immigration resulted from Lebanon's fairly tolerant attitude, as was evidenced when Lebanon granted residency permits and sometimes even Lebanese citizenship to Jews fleeing persecution in Syria. Nevertheless, there were incidents of rioting and incitement around the time of the establishment of the State of Israel. Only after the Six-Day War and the outbreak of the civil war of 1976 did Jews feel compelled to emigrate en masse.In the past two decades, the political climate has radicalized, and the remaining Jews are left in a tenuous and vulnerable position.

Communal And Religious Life

Nearly all of the remaining Jews are in Beirut. Because of the current political situation, Jews are unable to openly practice Judaism. In Beirut there is a committee that represents the community. Prior to 1976, there had been two schools and two synagogues in Beirut, and a school in Sidon.

Relations With Israel

Between 1976 and 1982 the PLO occupied an area in South Lebanon and launched attacks from this location. The Lebanon War was fought by Israel in 1982, in order to destroy this terrorist base. Israel supports the South Lebanese Army which is mainly composed of local Christians, and continues to maintain a presence in South Lebanon; skirmishes between the IDF and the radical Islamic movement Hizbollah are frequent occurrences. Aliya: Since 1948, 4,062 Lebanese Jews have emigrated to Israel.

Kosher Food

For up to date information on Kosher restaurants and locations please see the Shamash Kosher Database

Only One Jew Remains in Yemen, U.N. Says

A lone Jewish person remains in Yemen, down from seven a month ago, according to a new United Nations report about the treatment of religious minorities in conflict zones.

The report, which was published by the U.N. special rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, described the treatment of religious minorities around the world. “In recent years, the rise in situations of conflict and insecurity has impacted communities of every religion or belief system, subverting their enjoyment of fundamental human rights, including freedom of religion or belief,” the report noted.

Although the report did not name the one Jewish individual remaining in Yemen, “that Jew is undoubtedly Levi Salem Musa Marhabi, who has been illegally imprisoned and tortured by Ansar Allah since 2016,” said Jason Guberman, executive director of the American Sephardi Federation, referring to the Houthi rebel forces by their official name, Ansar Allah.

Yemen’s Houthis have imprisoned Marhabi since 2016, despite court orders demanding his release. American officials have also issued calls for Marhabi’s release. “We understand the Houthis continue to detain Mr. Marhabi despite our calls, and those by the international community, for his release,” a State Department spokesperson told Jewish Insider last month.

According to the U.N. report, the Houthis “coerced Jewish and Baha’i communities into leaving — blackmailing them by arbitrarily detaining religious leaders, influencers and community members.” The goal of such actions, Ahmed Shaheed, the special rapporteur, wrote, is “to weaken the community’s morale, resilience, or cohesion.”

As a result of the Houthis’ treatment of religious minorities, “only one Jew reportedly remain[s] in the country, from a population of approximately between 1,500-2,000 Jews in 2016.”

In its discussion of Yemen, the report also called out the Houthis’ treatment of the country’s Baha’i population. “A Houthi leader in Yemen has described Baha’is as Israeli spies, effectively making the community targets for harm,” the report stated.

The U.N. report described instances of human rights violations against religious minorities in conflict zones around the world, including Myanmar’s perpetration of genocide against the Rohingya and the targeting of Christians and Jehovah’s Witnesses by armed separatist groups in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine.

“We commend his efforts and support[the special rapporteur’s] references to Houthi violations against religious minorities,” said Abdullah Ali Fadhel Al-Saadi, Yemen’s permanent representative to the United Nations, at a Thursday meeting of the U.N. Human Rights Council. “Like all other extremist terrorist organizations, the Houthis have undertaken violations of the rights of Jewish and Bahai societies. The Houthis have expelled many minorities, blackmailed them, and have arbitrarily detained their leaders and seized their work and properties.”

The man who flew 120,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel | Lyn Julius | The Blogs

Jews with roots in Iraq are today the third largest community in Israel – after the Soviet and the Moroccan. Did you ever wonder how they got there?

The mass aliya of some 120,000 Iraqi Jews between 1950 and 1951 is attributable largely to the efforts of one man — Shlomo Hillel, who died on 8 February 2021, aged 97.

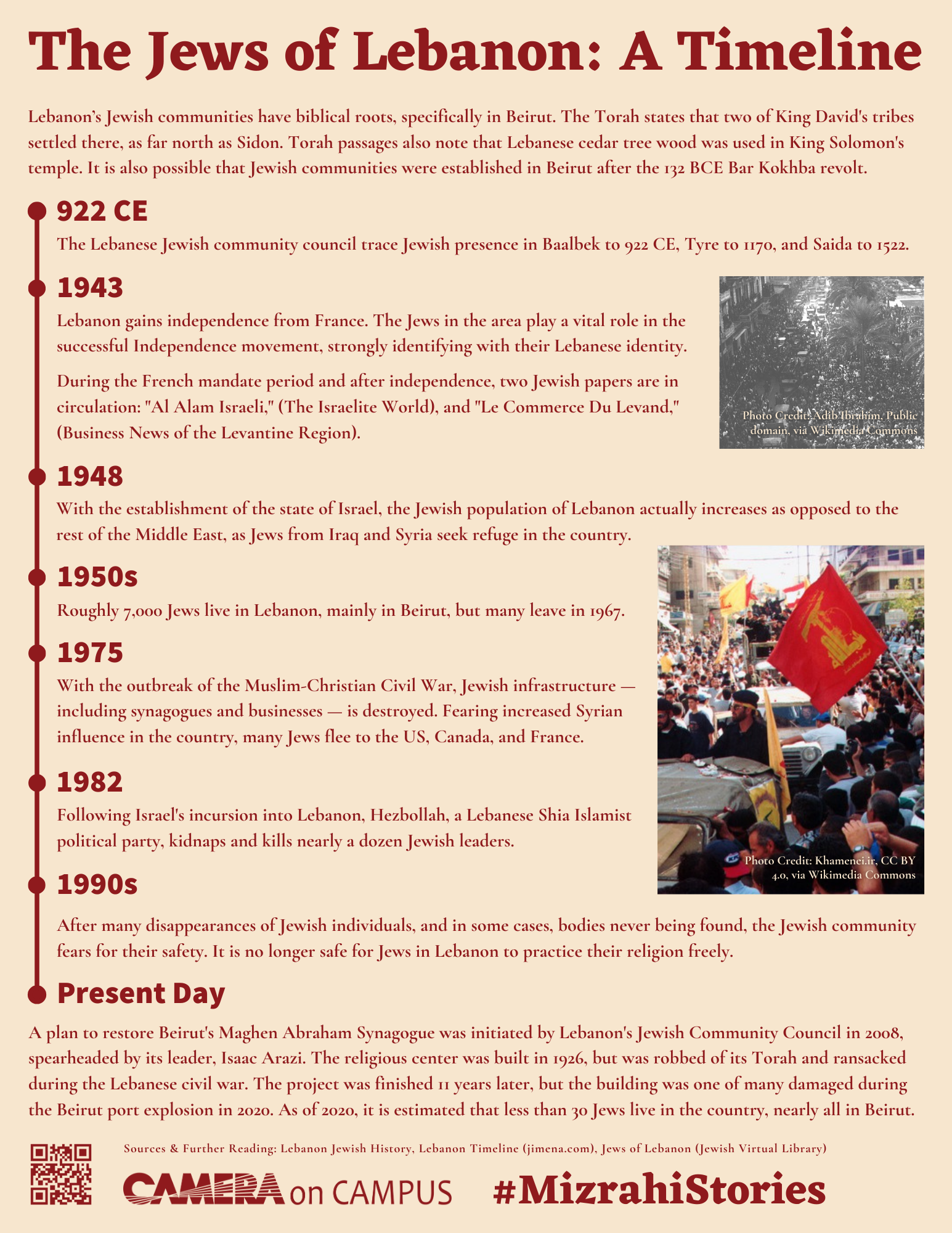

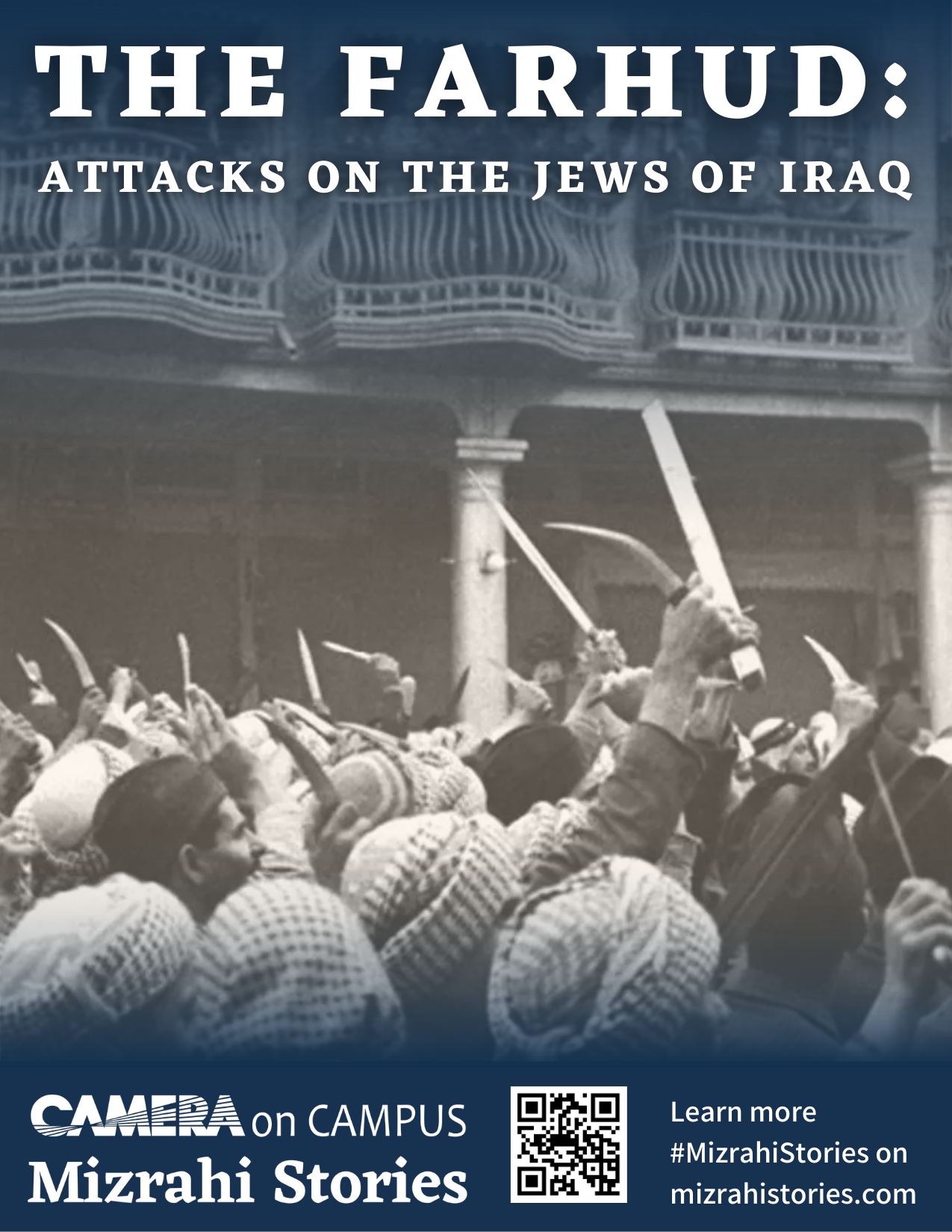

The Jews of Iraq, the oldest diaspora in the world, had been through troubled times in the 1930s and 40s. Hundreds were murdered in the Farhud massacre of 1941, and the Arab war against the fledgling state of Israel had led to persecution, extortion and the criminalisation of Zionism. In defiance of a travel ban, 12,000 Iraqi Jews were smuggled over the porous border into Iran. Working with a Jewish-born priest, Alexander Glasberg, to get the Jews French visas for Israel, Shlomo bribed Iranian policemen to look the other way. Posing as a member of the crew, Shlomo Hillel arranged the first test flights, piloted by American freelance pilots, to smuggle 100 Jews from Iraq to Israel, Operation Michaelberg.

Before Israel had an official army, Shlomo led the construction and operation of a secret bullet factory, under the noses of the British. The factory, known as the Ayalon Institute, was built beneath the laundry room of a kibbutz in Rehovot.

When the Iraqi government briefly lifted the ban on immigration in 1950 on condition that the Jews relinquished their citizenship, Baghdad-born Shlomo returned to Iraq as a Mossad agent to facilitate their airlift, dubbed Operation Ezra and Nehemiah. Aged 23, he posed as Richard Armstrong, the British representative of Near Eastern Airlines, to negotiate with the Iraqi government. Throughout the meeting he shifted in his seat, fearing he might be recognised by his cousin, the leader of the Jewish community. (He wasn’t). Shlomo Hillel published his story in Operation Babylon.

Shlomo was the youngest of 11 children of an Iraqi-Jewish merchant importing goods from India, Japan and Manchester. Iraqi Jews were not generally Zionist, but until the rise of pro-Nazi feeling in the 1930s, there was a small Zionist movement, Achi-ever, where Shlomo and his brothers learned Hebrew. In 1934, aged 11 on a family visit to Palestine, Shlomo insisted on remaining with two elder brothers, attending the prestigious Herzliya Gymnasium in Tel Aviv. Having lived through the massacre of Assyrian Christians in Iraq in 1933, Shlomo’s father had a sense of foreboding: ‘If they do this to Iraqi Christians, what will they do to Jews? He moved the rest of his family to Israel.

A founder of kibbutz Ma’agan Michael, Shlomo Hillel married Temima, who came as a refugee from Europe on the Patria. He reluctantly embarked on a political career, serving in seven Knessets, becoming a Minister and Knesset speaker. He also served as Israeli ambassador to several African countries, and was awarded the Israel prize in 1988. But he was always modest about his achievements.

Later Shlomo Hillel was involved in the mass emigration of Jews from Ethiopia. The wheel came full circle when his son Ari fell in love and married an Ethiopian girl. When asked what he thought of the match, Shlomo said he was delighted. The Jewish people was completing the ‘Ingathering of the Exiles’.

Attacking Israeli Food? Your Racism Is Showing

Every Friday, my mother and her 11 brothers and sisters have lunch at my grandmother Hela’s home in Petah Tikva.

There, they find dozens of pots simmering on stoves filled with various dishes that had been prepared with love all day — some even overnight. These Fridays, my grandmother serves her famous kubbah, a Mizrahi dish that takes hours to prepare. Each grandson picks his kubbah’s flavor: okra, pink beets, pumpkin, spicy kubbah and more.

My grandmother always insists on sending my mother home with a bag of homemade hummus, amba (Iraqi spicy mango spread), hard-boiled eggs, fried eggplants and arok, (fried vegetable patties.) On Shabbat morning, we stuff all of these flavors into pita bread, creating a sabich, a traditional Iraqi Jewish sandwich.

My Iraqi mother honors her mother by cooking traditional Iraqi Jewish dishes. She has this in common with my Tunisian father and his 15 siblings, who also prepare their grandmother’s North African Jewish recipes.

Recently, anti-Israel activists launched a campaign to obliterate my grandmother’s Shabbat lunches. Or so it felt that way.

This attack was in reaction to a post on a website called Hey Alma, which asked people to announce their “unpopular Jewish food opinions.”

“No such thing as Israeli cuisine!” posted one Ashkenazi Jew. “Israeli salad and Israeli couscous aren’t Israeli, they’re Arab foods that have been culturally appropriated,” wrote another Ashkenazi anti-Zionist, receiving more than 1,000 “likes.”

By declaring Israeli cuisine doesn’t exist, these anti-Zionists are stealing Mizrahi recipes and delivering them to regimes that ethnically cleansed us.

Saying Israel has no food or culture is the politically correct way of being racist toward Mizrahim.

After the majority of Mizrahi Jews fled for their lives to escape anti-Semitic regimes throughout the Middle East, they resettled in Israel. We identify our food as Israeli because as members of the Jewish state we can cook it without the fear of being massacred.

Now anti-Zionists proclaim that our cuisine is stolen from the Arab world.

This claim is laughable at its core; the Arab world is an imperial-colonial project designed to erase minorities and their culture in the Middle East and North Africa. The land where my grandmother learned to cook with her grandmother was not Arab — it was once a multi-ethnic state.

But in their quest to strip Israel of its culture, these activists dubbed my grandma’s recipes that she brought from Baghdad as appropriated from the Arab world that butchered her family.

By accusing Mizrahi Jews of cultural appropriation, these extremists essentially deny 53% of Israeli Jews who came to Israel from the Middle East and North Africa, the right to partake in our heritage. It is racism and anti-Semitism for the price of one.

Saying Israel has no food or culture is the politically correct way of being racist toward Mizrahim. These bigots aren’t just stealing our culture, they are claiming we have none.

It’s not the first time Hey Alma contributed, deliberately or not, to this anti-Mizrahi erasure. The website frequently posts about Ashkenazi food and culture but seldom posts about Mizrahim, our food, or our heritage.

The goal of this campaign? Dehumanization. No nation lacks cuisine. Deprive Jews and Israelis of a culture, and you deprive us of our humanity.

Perhaps that is the root of the divide between some American Jews and Israelis: apathy via dehumanization.

American Jews become anti-Zionists because they struggle to empathize with Israelis. They wish we ate bagels and lox instead of hummus and sabich, listened to Barbra Streisand and not Omer Adam. They are alienated by how Israel, unlike most American Jewish spaces, adopts Mizrahi culture. They wish our national language was Yiddish and not Hebrew and Arabic, that we cared more about their interpretation of tikkun olam instead of our survival.

Along with dishes from all global Jewry, Mizrahi cuisine is a part of the emerging Israeli cuisine, and that’s a hard fact for anti-Zionists to swallow.

Journalist Forced To Flee After Capturing Rare Images Of Iranian Jews Publishes Book

JTA — Jewish prayer in a mosque. Hookah smoke in a kosher kitchen. Hebrew school study under portraits of ayatollahs.

When former Associated Press photographer Hassan Sarbakhshian spent almost two years between 2006 and 2008 among the Jewish communities in Iran, those are some of the images he collected for a book project. The photographs offer a rare look inside Jewish homes, synagogues and other spaces, which the Jewish community normally keeps fairly locked down to outsiders.

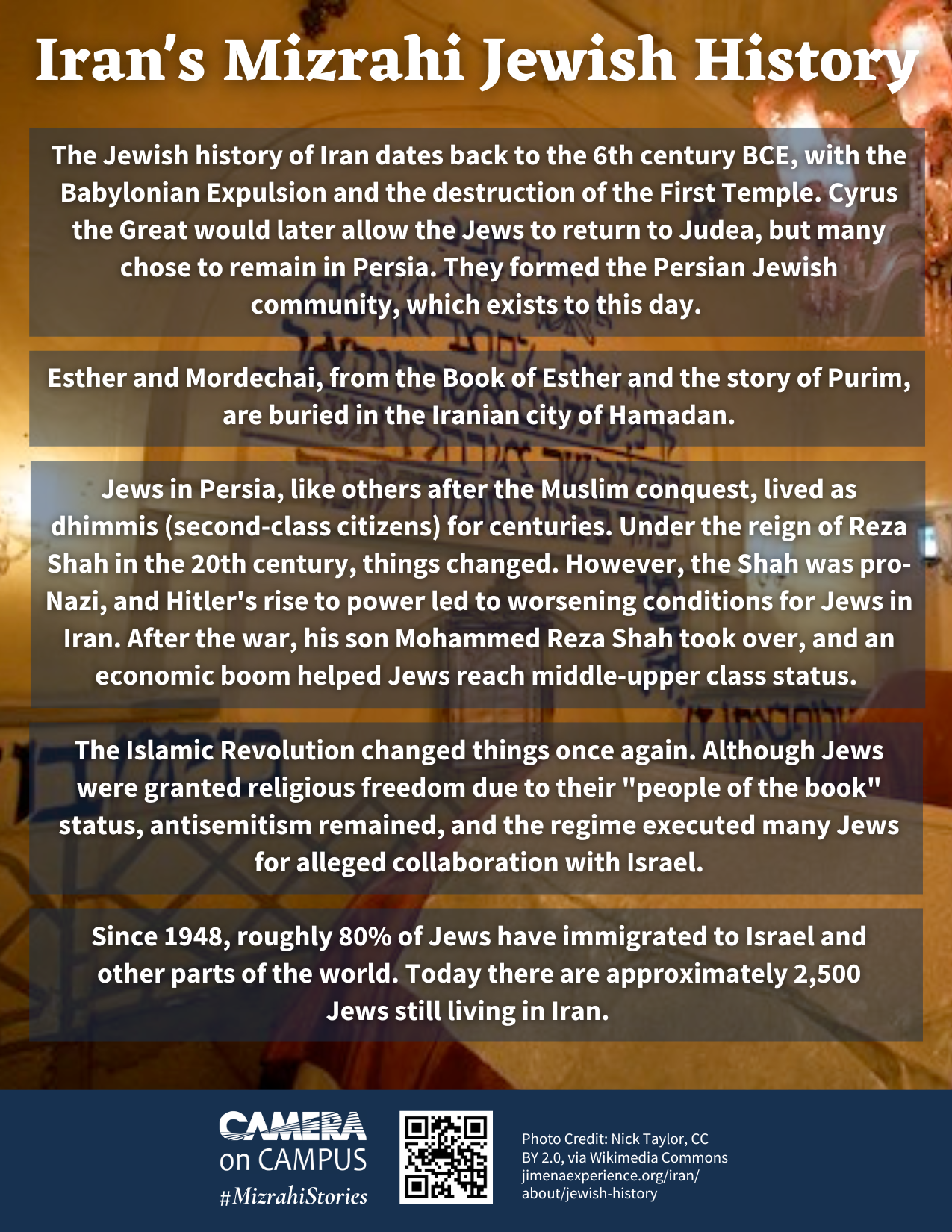

In Iran, a nation whose post-1979 revolution government regularly calls for the violent destruction of Israel, Jews are famously allowed to practice their religion freely and feel a strong connection to their country. There is a permanent Jewish representative in parliament.

But when Sarbakhshian submitted the book to Iran’s culture ministry for publication, he ran up against the country’s pervasive anti-Zionist culture.

The ministry argued that he was an agent of Israel promoting anti-Islamic values. They forced him out of working for the AP, and he eventually began to fear for his and wife’s safety. He and his wife, Parvaneh Vahidmanesh, a journalist and human rights activist who was involved in the project, moved to Virginia

Nearly 15 years after taking his last photos for the book, “Jews of Iran: A Photographic Chronicle,” which will finally be published on Tuesday by Penn State University Press, Sarbakhshian still calls the project that led to the ordeal one of the best experiences of his life.

“We traveled to more than 15 cities on a bus with [Iranian Jews]. We laughed with them, we ate with them. We lived with them, actually,” he said.

The Last, Last Jew? Simentov Relative Flees Afghanistan after Taliban Takeover

AP — For years, Zebulon Simentov branded himself as the “last Jew of Afghanistan,” the sole remnant of a centuries-old community. He charged reporters for interviews and held court in Kabul’s only remaining synagogue. He left the country last month for Istanbul after the Taliban seized power.

Now it appears he was not the last one.

Simentov’s distant cousin, Tova Moradi, was born and raised in Kabul and lived there until last week, more than a month after Simentov departed in September. Fearing for their safety, Moradi, her children and nearly two dozen grandchildren fled the country in recent weeks in an escape orchestrated by an Israeli aid group, activists and prominent Jewish philanthropists.

“I loved my country, loved it very much, but had to leave because my children were in danger,” Moradi told The Associated Press from her modest quarters in the Albanian town of Golem, whose beachside resorts have been converted to makeshift homes for some 2,000 Afghan refugees.

Moradi, 83, was one of 10 children born to a Jewish family in Kabul. At age 16, she ran away from home and married a Muslim man. She never converted to Islam, maintained some Jewish traditions, and it was no secret in her neighborhood that she was Jewish.

“She never denied her Judaism, she just got married in order to save her life as you cannot be safe as a young girl in Afghanistan,” Moradi’s daughter, Khorshid, told the AP from her home in Canada, where she and three of her siblings moved after the Taliban first seized power in Afghanistan in the 1990s.

Camera Op-Ed: Egypt, Israel And The Arc Of History

On Sept. 13, 2021, Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett met with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi in Sharm El-Sheikh in the Sinai Peninsula. The event was the first public invitation for an Israeli premier to meet on Egyptian soil in a decade. But while the meeting was well covered by Western news outlets, many in the media failed to place it in its proper historical context. Indeed, coming less than a month before the fortieth anniversary of the Oct. 6, 1981 assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, it also offers an opportunity to take stock of Israeli-Egyptian relations, past, present and future.

At the dawn of Israel’s 1948 recreation, Egypt was the Jewish state’s foremost opponent. During Israel’s War of Independence, it was Cairo that supplied the bulk of the forces. And it was Egypt, the preeminent Arab power of the day, that most concerned many Israeli leaders.

Indeed, Egypt had played an important role in opposing Zionism in the years leading up to Israel’s 1948 War of Independence. The Arab League itself was announced following a meeting between seven Arab nations in Alexandria in the fall of 1944, with a pact being signed on March 22, 1945 in Cairo. And Abd al-Rahman ‘Azzam, an Egyptian, was announced as the League’s first secretary-general. By December 1945, the League had announced an economic boycott of the Jewish community in British-ruled Mandate Palestine.

Israel’s victory over Egypt in 1948 didn’t dissuade Cairo’s leaders from future aggression. Instead, the country’s defeat led to the toppling of King Farouk and the rise of Gamel Abdel Nasser. As a young Colonel during the war, Nasser’s memoirs noted the “bewilderment and incompetence” that “characterized our high command.” Egypt’s poor battlefield performance, and the apparent “spirit of indifference” among the ruling monarchy, helped Nasser and the Free Officers Movement topple Farouk in 1952.

The Egyptian strongman, however, remained focused on attacking the fledgling Jewish state. Egypt, like other Arab states, refused to recognize Israel and merely signed an armistice. But Cairo continued its war, training and arming fedayeen (“one who sacrifices himself”) to carry out cross-border terrorist attacks.

An Egyptian military captain named Mustafa Hafez organized the fedayeen. Hafez and Salah Mustafa, the Egyptian military attaché in Amman, recruited and trained no fewer than six hundred fedayeen, who bombed train tracks, blew up water pipes and roads, committed arson, and murdered as many as one thousand Israeli civilians between 1951 and 1955. And, as Michael Doran noted in his 2016 book Ike’s Gamble: they “were not so much forming a new terror network as resuscitating an old one—the network of the Palestinian nationalist leader Haj Amin al-Husseini, the mufti of Jerusalem, who at that time was living in exile in Cairo.”

“The proxy squads,” the journalist Ronen Bergman wrote in his book on Israeli intelligence, Rise and Kill First, “were considered a huge success.”

Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) attempted to carry out retaliation raids but, as Bergman noted, they “repeatedly failed,” and “by the middle of the 1950s, Hafez was winning.” Accordingly, in June 1953, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion pushed for the establishment of a commando unit, called Unit 101, to carry out operations and establish deterrence. Meanwhile, Israeli military intelligence operatives successfully targeted Hafez and Mustafa with mail bombs. Terrorist incursions into Israel were dramatically reduced.

Nonetheless, Egypt remained Israel’s primary adversary.

Home to many Nazi war criminals and Third Reich scientists, Cairo worked assiduously to develop missiles capable of hitting Israel and, eschewing outreach from the U.S. and others, Egypt began to receive arms and support from the Soviet Union and its satellites. The Middle East had been transformed into a Cold War battlefield, with Israel and Egypt as the stand-ins.

The growing tensions, and Nasser’s July 1956 decision to nationalize the Suez Canal, prompted Israel to collude with the U.K. and France to attack Egypt. Israel’s military campaign was a success—aided in no small part by two monumental intelligence coups. At the war’s opening, Israel managed to shoot down a plane carrying much of the Egyptian General Staff.

And after successfully occupying the Sinai Peninsula, Israeli intelligence found a building in Gaza City that contained the “intact card file of all the Palestinian terrorists that Hafez and his men had deployed against Israel in the five years preceding the Sinai campaign,” a veritable hit list, as Bergman noted. Militarily, Nasser had suffered a tremendous blow.

But in a move that he would later come to regret, Eisenhower forced the British, French and Israelis to withdrawal, handing Nasser a major propaganda victory against the West.

Yet, as declassified CIA documents show, Egypt continued to work against Israel and U.S. allies in the region. One revelation in particular stands out and is missing from historical accounts.

An Agency timeline of the activities of Amin al-Husseini, the founding father of Palestinian nationalism, noted that Husseini and “Egyptian Minister Anwar Sadat planned [an] assassination attempt King Saud [of Saudi Arabia] in mid April [19]57.” A “Palestinian assassination expert” with the last name of Shahin “received a bomb in Jidda, passed it to A’bdallah Faysal,” a “member of the Saudi royal family who placed it in the king’s bedroom.” The plan, however, was discovered, but “hushed up” because of Faysal’s involvement. The document also notes that Husseini was involved in an aborted plot to plant a bomb at the U.S. consulate in Jerusalem on Aug. 8, 1957.

Husseini’s involvement, and the plot itself, isn’t surprising.

The post-Suez Crisis Middle East experienced increased instability. The U.S.-backed Hashemites in Iraq were overthrown in a bloody coup in 1958 and the U.S. felt obliged to send troops to Lebanon that same year. King Saud himself would cancel a June 1957 trip to Jordan as he was “deeply impressed by recent signs of Eygptian and Palestinian conspiracy against” the two Arab monarchies, according to a June 4, 1957 CIA bulletin. Another Aug. 6, 1957 Agency report noted that Nasser planned to assassinate Jordan’s King Hussein and Lebanon’s President Camile Chamoun and a “similar attempt against Saud is having ‘organization difficulties,’ but Nasser hopes for a ‘successful conclusion’ within the next six months.”

And, perhaps not coincidentally, Saud plotted, and failed, to assassinate Nasser in 1958, leading to his relinquishing the throne.

Although he had previously, and successfully, solicited Saud for money for his anti-Israel activities, Husseini was seeking to “form a new government of Palestine and Gaza,” which the Egyptian Ambassador supported but King Saud “will not accept.” In April 1957, a declassified CIA cable notes, a “Palestinian who is said to have participated in the assassination of Jordan’s King Abdullah in 1951” was caught in Riyadh with a “cache of weapons and explosives.”

A fan of Zane Grey novellas set in the American West, Sadat was, nonetheless reared on anti-Western nationalism. As a young military officer he was a member of the fascist Green Shirt movement in Egypt and during World War II he provided the Nazi General Erwin Rommel with intelligence on then British-controlled Egypt.

Nasser himself would continue to make war against the Jewish state—and to use the Palestinian issue as a cudgel. It was Nasser’s Egypt that established the Palestine Liberation Organization in 1964. Egypt’s sound defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War repudiated Nasserism, but the Egyptian strongman himself was unbowed. In the years before his death in 1970 at the age of fifty-two, Nasser promoted Yasser Arafat’s takeover of the PLO, negotiated the 1969 Cairo Agreement that established Lebanon as a base for the PLO, and launched the so-called War of Attrition.

It would be up to his successor, Sadat, to change course. Sadat sent signals—many of which were initially missed—that he sought to move from the Soviet camp to that of the United States. Egypt’s strong performance in the 1973 Yom Kippur War had, in Sadat’s mind, redeemed earlier losses. And Sadat knew that a rapprochement with the U.S. required a change in posture toward Israel.

Sadat would, along with Israeli premier Menachem Begin, win the Nobel Peace Prize for signing the Camp David Accords in 1978 and recognizing Israel. The move shattered the united Arab front against Israel, but it also led to Egypt’s ten-year-long suspension from the Arab League and, forty years ago this October, the murder of Sadat by Islamist terrorists.

The cold peace between the two nations has held, withstanding Sadat’s assassination, as well as the fall of his successor Hosni Mubarak in 2011 and the brief rule of the Muslim Brotherhood. But, as Simone Ledeen, a former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense, recently noted, it is not to be taken for granted. History tells us that she’s right.

(Note: A slightly different version of this article appeared as an op-ed in The National Interest on Sept. 21, 2021)

Sean Durns is a Senior Research Analyst for the Washington D.C. office of CAMERA. With a background in the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence, he worked for several think tanks and for a former high-ranking Pentagon official before joining CAMERA. His articles regularly appear in a variety of media outlets, including The Washington Examiner, The Washington Times, The Hill, The Jerusalem Post, and The Washington Jewish Week.

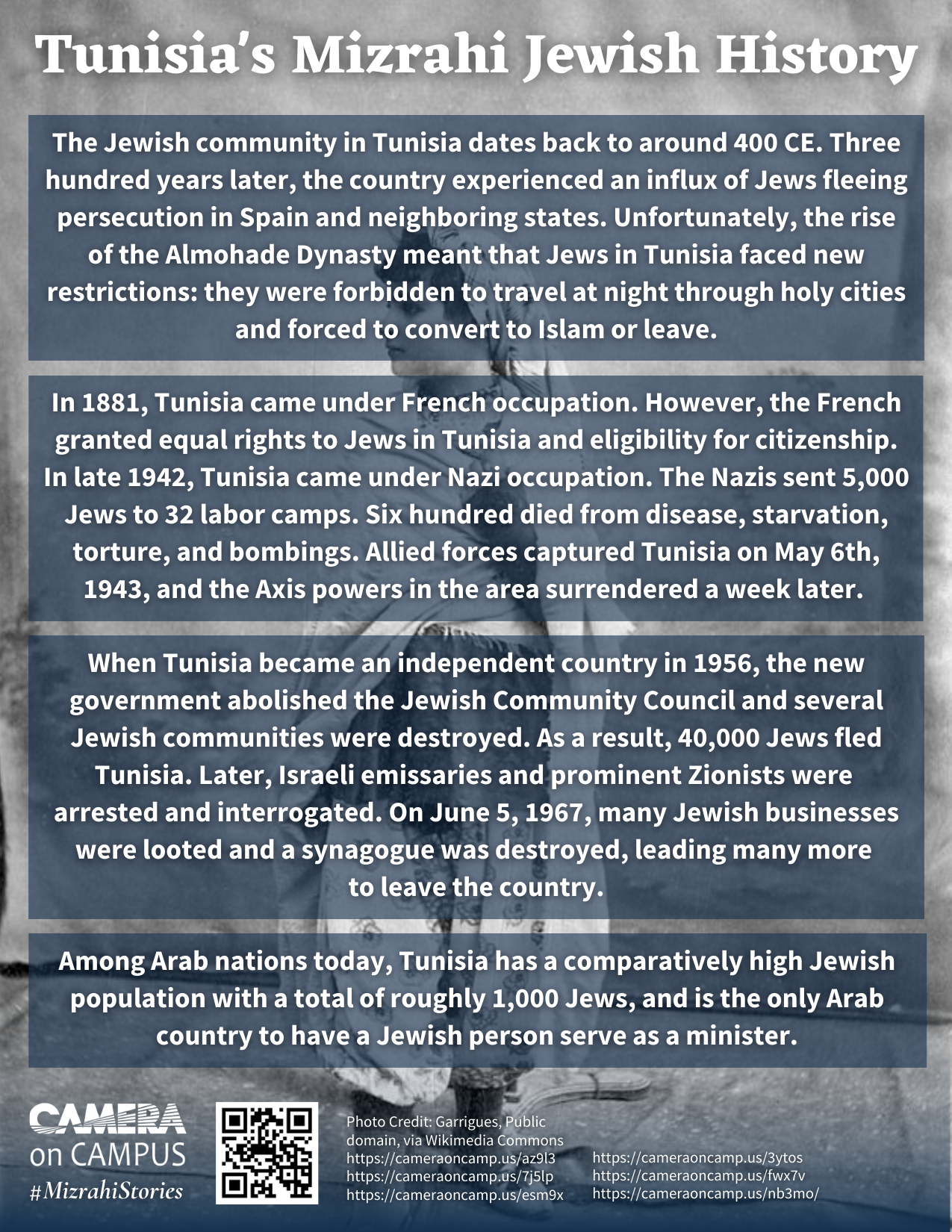

The Last Remnant of Arabic Jewry: My Recent Trip to Djerba

The tiny island of Djerba remains the largest outpost of Arabic-speaking Jews today. Found off the coast of Tunisia, Djerba boasts a small but steady Jewish population of around 1,200 people. On the surface, a description of Djerba might resemble what one might see on a present-day tour of other Sephardic countries like Morocco. However, after visiting Djerba with my father this past June, I discovered that Djerba is not merely a unique side of Sephardic Jewish history or the artifacts of a lost community. In fact, Djerba is a thriving community infused with youth and culture, effectively serving as a window into the otherwise forgotten group of Arabic-speaking Jews.

While massive populations of Jews once inhabited the regions of North Africa and Arabia, in the twentieth century, following persecution in the wake of events like the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, many of them were forced to flee to countries like Israel, the United States and France. Despite this mass emigration, the Djerba community has successfully maintained its 2,000-year-old community, its rich Sephardic and Tunisian culture and its fusion of tradition and modernity.

Aside from its remarkable endurance, the Djerbian Jewish community is distinct in a multitude of ways, even from the communities of nearby North African countries and mainland Tunisia. This unique nature manifests itself most clearly within the island’s minhagim. For example, while Ashkenazic Jews outside of Israel only recite Birkat Kohanim on holidays and Sephardim and Israelis perform it every day, Djerbian Jews say it every Shabbat. Additionally, the person taking the Torah out of the Aron removes his shoes, and in the great El Ghriba shul, the island’s oldest shul and where tourists from all over the world come to visit, the practice is to take off one’s shoes before entering the sanctuary. Djerba is also the only place in the world where the shofar is blown before Shabbat, notifying the residents to stop working. Interestingly, except for when they are eating or davening, most Djerbian Jews do not wear a kippah outside of the Jewish area, despite all of them being Shomer Shabbat (observant of the Sabbath), most going to minyan and many learning Torah regularly. While some people may have heard of Djerba for its famed city of Kohanim, today, only a few families of Kohanim remain, and remarkably, there is not a single Levi on the entire island.

What I found most interesting is the community’s simultaneous adaptation to modernity while in some areas holding strong to the practices of its ancestors. On the one hand, one might assume that if most people have smartphones that the same acceptance of modernity would apply to the educational system as well. However, most boys in the cheders were not learning any secular studies. On the other hand, many yeshivas in the U.S. and Europe that do not place an emphasis on secular studies do not teach Hebrew well either; however, the schools in Djerba teach everyone to speak modern Hebrew fluently, which made it very easy for us to make conversation with everyone.

The practices regarding the interactions between men and women present another fascinating aspect of the community. While the Djerbian custom of unmarried men and women not speaking to each other and arranged shidduchim is found to various degrees in many other contemporary communities, the custom of couples not interacting at all within a one or two-year engagement period is not found even in the most Hasidic communities of Brooklyn. In general, Djerbian women do not go to shul, and many of the shuls do not have women’s sections. Ironically, though, the Djerbian women are more modern than one might have anticipated. For instance, some women spoke to us at Shabbat meals, and the girls learn English and other secular studies in school.

Also of significance is the Djerbian Jews’ nuanced perspective on the State of Israel. First, despite many having family members in Israel and all supporting the existence of a Jewish state, Djerbian Jews discourage those on the island from making aliyah. While everyone in the Djerba community keeps Shabbat and has a strong connection to Judaism, the same cannot be said about those who make aliyah. The Djerbian perspective on Zionism is a friendly reminder that Israel, with all of its virtues, does not absolutely guarantee religious observance for all its inhabitants. On the other hand, although Jews in other countries maintain a more reserved public support for Israel, the same cannot be said about the Jews of Djerba. Not only do they say Mi She’beirachs for the Israeli government and army, but when Yom Haatzmaut comes around, they do not say Tachanun the days before and after in addition to on the holiday itself. Therefore, in spite of no Tunisian diplomatic relations with Israel, the Tunisian President proclaiming that any ties with Israel is “high treason” and Israelis being forbidden to travel to the country except for during the Lag Baomer season, the Jews of the island still preserve a pro-Israel sentiment, albeit in a manner which is slightly complex.

Similarly, notwithstanding cases of trouble in the past, the Jews and Muslims are very friendly with each other, and throughout my trip, I never felt unsafe. One day our tour guide, Adir, took us to the local shuk where we ate at a kosher restaurant, saw his jewelry store and met his Muslim co-worker, Farhid. There are a few armored vehicles and soldiers standing by the entrance to the Jewish neighborhood, and when thousands of Jews from all over the world flock to the island for the annual Lag Baomer festivities, the government provides heavy security.

My favorite part of the trip was undoubtedly Shabbat. We ate at an older gentleman’s house for Friday night dinner; the house was very small but decorated with the azure blue found throughout the island and all of the fourteen shuls. We had a beautiful meal, in Hebrew, and spoke with our host about his relationship with Rav Meir Mazuz, a well-known Tunisian Rosh Yeshiva in Bnei Brak. For dessert, we cracked open some unripe green almonds and had some abnormally shaped peaches.

Throughout Shabbat, most people walk in circles around the small Jewish neighborhood and talk with each other. In the early afternoon, we sat in a Beit Midrash adjacent to one of the shuls and asked the nearby chacham (sage) various questions about Djerbian minhagim. At 4:15 in the afternoon, we finally sat down for Shabbat lunch and enjoyed talking to Adir and his two brothers, some of the few English speakers in the community. The food and dips were spicy but not too spicy, and the best dish was the chamin, Sephardic cholent made in the communal oven. Spending Shabbat in Djerba was truly eye-opening for me; I don’t believe I could say that I really experienced the community without it.

There are so many more customs and interesting facts about this community, and very little has been published in English that successfully depicts the unique nature of the community. However, even a thorough article cannot really illustrate the Djerbian community, and it really takes being there in person to understand the lives of the Jews on this small island. While many Sephardim do not fall into the neat categories of religious levels and community affiliations often used by Ashkenazic Jews, this is especially true of Djerbians. The community of Jews in Djerba is like no other, and I cannot wait until I return.

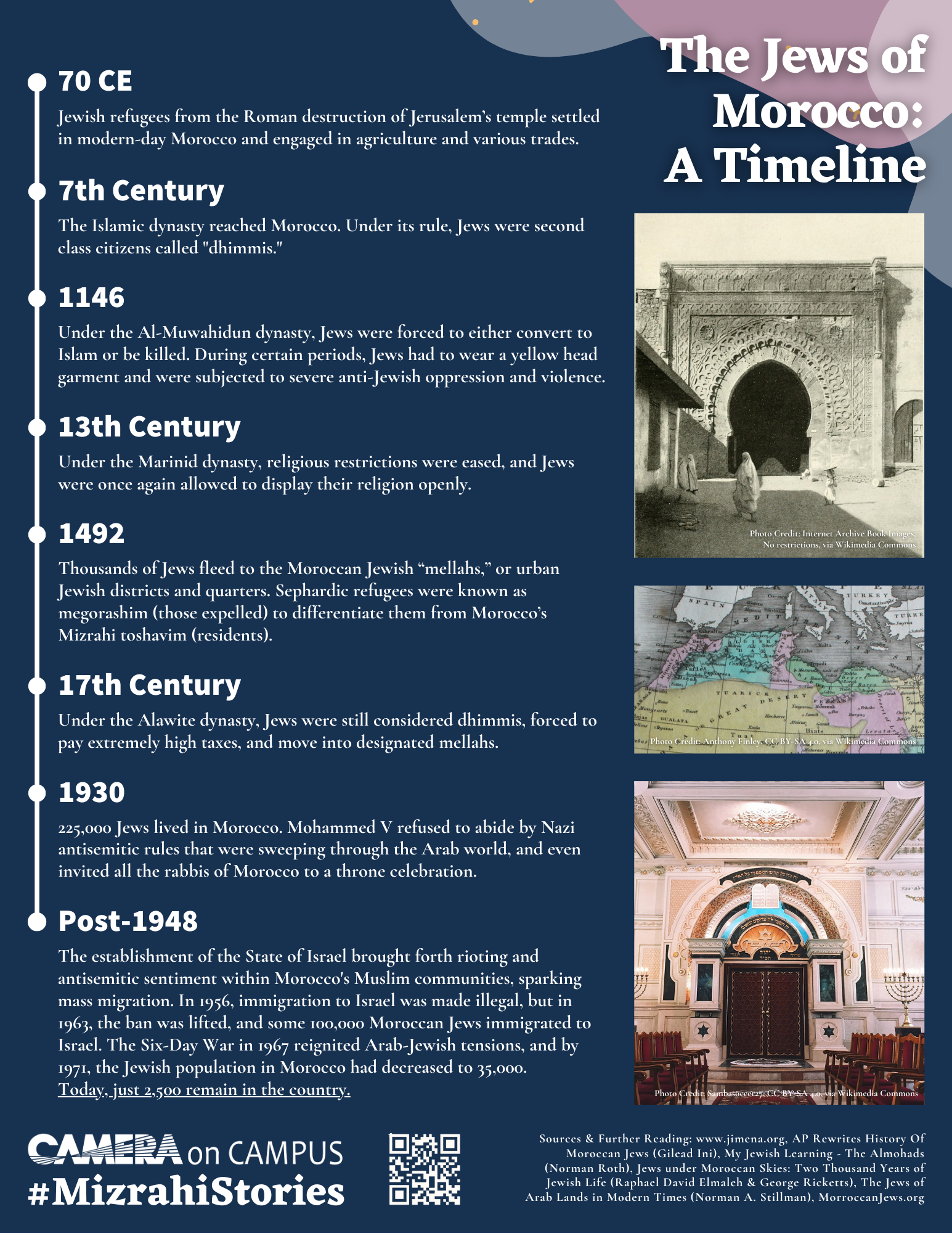

Still Living: Remembering Morocco’s Jews

When I think about Israeli culture, I think of startups, I think of gorgeous museums with modern art exhibits, of Sabich, falafel, and hip new musicians, of the Tel Aviv boardwalk and the new lineup of hit Israeli TV shows on Netflix. Israel has a rich culture, and yet often we see it as separate from all of the Jewish history that occurred outside the Holy Land itself. For thousands of years, the Jewish people have lived in the Diaspora, outside the land of Israel. From the moment the first Jews were exiled from the land of Israel in 600 BC a myriad of new cultures with incredible facets began to form. Judaism today is a combination of a diverse array of experiences, traditions and rich cultural heritage that all come together to create a vibrant culture and many deeply rooted traditions, connected to countries the world over.

Growing up, I learned in Jewish schools and at home about the dispersion of Jews from the land of Israel, most prominently following the Roman conquest of the land. In my classes we spoke in depth about the migration of Jews to countries throughout the world, talking about the adaptation of the Jewish religion to life outside the holy land, about the famous sages, and about the golden eras for Jews throughout Europe and later in the Muslim kingdoms of Iberia and North Africa. However, the past century of Jewish history has played an incredibly influential role in my Jewish education. As I look back I think of the culmination that was going on the March of the Living. In one trip we marched out of Auschwitz in Poland and subsequently flew to Israel to celebrate our survival and return home to the land of Israel. This past summer I went on what I felt to be a parallel journey to my experience of the March of the Living — in Morocco.

I spent two months visiting different parts of Morocco, and in each place, I would wait to hear the awkwardly inserted bit about the Jews. For the most part, these were honorable mentions. Like “the Jews lived here, close to the king’s palace” or “the Muslims, the Berbers, and the Jews were good friends and always got along well”, and importantly, “the Moroccan constitution gives Jews special permission to be tried in Jewish courts according to Jewish law, a right which is not even present in Israel.” It was a thrill, learning a new and enchanting side of the history of my people.

The king of the country has a personal connection with the Jewish community. And yet, most of the references to the Jewish community were solely historical. Seldom did we hear anything spoken about the contemporary community.

Sadly, this is because only around one percent of Morocco’s pre-1948 Jews remain. In a country that was once home to more than 250,000 Jewish individuals only a community numbering less than 5,000 remains. I visited the historical towns and remaining communities and the dramatic loss was all too obvious. In the south, I visited a city by the name of Essaouira. On arriving, I looked for a place to spend Shabbat, hoping maybe to connect with a Jewish family or two that remained. I was shocked to discover that less than a century ago this dreamy seaside town had been home to a Jewish population large enough that they were not even considered a minority group. According to some locals, they had even been a majority in the town at some point. In the decades after 1948 Essaouira’s Jews left and the Jewish population dwindled into the single digits. Today many Jewish homes in the city are nothing more than rubble, while some of them are still used today as private homes, and one even as a hotel. Walking through the streets I saw the simple Jewish stars above door frames, among the few indications of the strong community that existed not so long ago in that very place.

Jews arrived in Morocco more than 500 years ago, living and working alongside their mostly Muslim neighbors. Within a few decades of the establishment of the State of Israel, they had all but disappeared. I have heard personal stories from friends of their family members being harassed. Even a story of a Jewish grandfather that was lynched by an angry mob in a small town in the Atlas Mountains. This parallels a larger trend throughout the Muslim world; it makes me think of the stories of friends’ parents who left their homes in the Middle East with nothing more than the clothes on their backs. Morocco was not alone in this sad wave of anti-Jewish hatred that swept the Arab world in the twentieth century. This hate led to the disappearance of 99.5% of the Arab world’s Jewish population. Many of these Jews were kicked out of their ancestral lands. They were forced to leave everything, and in many instances died trying to get their families to safety. Many of them, similarly to the world’s current refugees, experienced difficulties when restarting their lives in new countries.

For centuries, Jews had prospered in Arab societies with nothing more than occasional reminders that they were different. This all changed in 1948: the only difference being that they now had a new state they could call home. Many of these Jews did end up in the state of Israel but in 1948 Zion still remained an intangible dream. Yet they were suddenly the victims of hate because of a conflict far away. Standing in a large blue room, in the restored Chaim Pinto synagogue in Essaouira I felt one step closer to my roots. I conducted a prayer service, serving both as the cantor and as the crowd. I felt spiritually connected to the generations of Jews who had for centuries called Morocco home, and I felt closer to my own roots, as if I had just filled in another missing piece of the puzzle of Jewish history. I had the opportunity to experience a piece of the Jewish past that I believe every Jew should learn about. Just as I marched through Poland, learning about the Jewish communities that once were, so too opportunities should be expanded to expose more of our community to the incredible heritage and culture of Moroccan Jews, among all the other Jewish experiences that compose the Jewish community today.

A sonic journey into North African recorded music

Music remembers much of what history has forgotten, says Canadian assistant Professor of Jewish history Christopher Silver, who has just brought out his book ‘Recording history’, a fascinating journey through the soundscape of North Africa before decolonisation. It was a vibrant era which produced the singing sensation Habiba Messika; Jews and Muslims played together. Jewish musicians made such an impact that Jews had broadcast time allotted to them on Radio Tunis between 1919 and 1956. The MacGill Faculty publication interviewed Silver:

.png?u=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2F02dfoawcqsio%2Fatbax5hBVhldnm6EaTKpx%2F97f35a3ae5be8ffcf4715f6f9bd03e2c%2FBack__3_.png)

.png?u=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2F02dfoawcqsio%2F3BXycvefUNukOHsdiEMhi2%2F534ae9b8222c6c474db40efbb09c05da%2FFront__3_.png)

.png?u=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2F02dfoawcqsio%2F1w6NaQzvrXstsbwqkskTa0%2F68831f14f6751bfbbb331a067b714cec%2FBack__2_.png)

.png?u=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2F02dfoawcqsio%2F3zfKS0pBrNNiWOCIptl8H3%2F7868066b08eef668703a560233ecb2b9%2FFront__2_.png)

.png?u=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2F02dfoawcqsio%2F5jhuKjWMgYFKY49pGRuYjY%2F8e929d1c9b4587bf2f5febdc105ed7e2%2FBack__1_.png)

.png?u=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2F02dfoawcqsio%2F7DA8F9Fzo8QpMjetqEWGnC%2Fb5ee814bb9463f97b189946dd64d7cd7%2FFront__1_.png)

.png?u=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2F02dfoawcqsio%2F462KmbcBw0OYvSRSJcmHap%2F2b291e0f942297ebbcdc93544ea64d21%2FHebrew_Mizrahi_Campaign_-_Kavkazi_Infographic__1_.png)

.png?u=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2F02dfoawcqsio%2F3TZlujgLXnn0TXLSawfetA%2F4efb6be7e5d085a00e5590b8e0709978%2FHebrew_Mizrahi_Campaign_-_Syria_Infographic__1_.png)

.png?u=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2F02dfoawcqsio%2F7H0XnAfEWj4ptvzJPsNxw%2F6ac5ff373e4ab03c1cae288141d757d3%2FEnglish_Mizrahi_Campaign_-_Afghanistan_Infographic__1_.png)

.png?u=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2F02dfoawcqsio%2F2woY6GmuGq13LHfywCV4k4%2Ff0f70d90b54b6cd99e86007c58df0faf%2FHebrew_Mizrahi_Campaign_-_Bukharian_Infographic__1_.png)